When I first developed my teaching portfolio in 2021, I emphasised the importance of threshold concepts (Meyer and Land, 2003; see Knowledge). While I still think these concepts are the core building blocks for curriculum development, I have realised that the more fundamental guiding principle in my teaching is a “humanising pedagogy of engagement” involving engagement with students, engagement with content, and engagement of students with content (Olszewska et al., 2021). This plays out concretely through my four teaching goals.

When I teach, my goals are to:

- Get students excited so that they are motivated to engage with the subject matter.

- Give students the lay of the land, so that they have the bigger picture.

- Equip students to build up their own knowledge and skills, by showing them where to find and how to process the relevant resources.

- Treat each student as a person, a human being.

These goals are based on (Case, 2019) and (Brunton, 2020). I engage with students to create excitement for the work. I engage with the content myself, by being an expert researcher in my field, enabling me to distil the bigger picture. The ultimate goal is to get students to engage with the content themselves.

Excitement leads to engagement; without being excited, students won’t be motivated to engage with the material. I use humour to keep the class awake and make myself approachable. I share my own passion for the work (by being an area expert). I interleave slides with writing on the blackboard or a tablet. And I try to show practical demos and examples to spark an interest, e.g. demos using language and music (see Students).

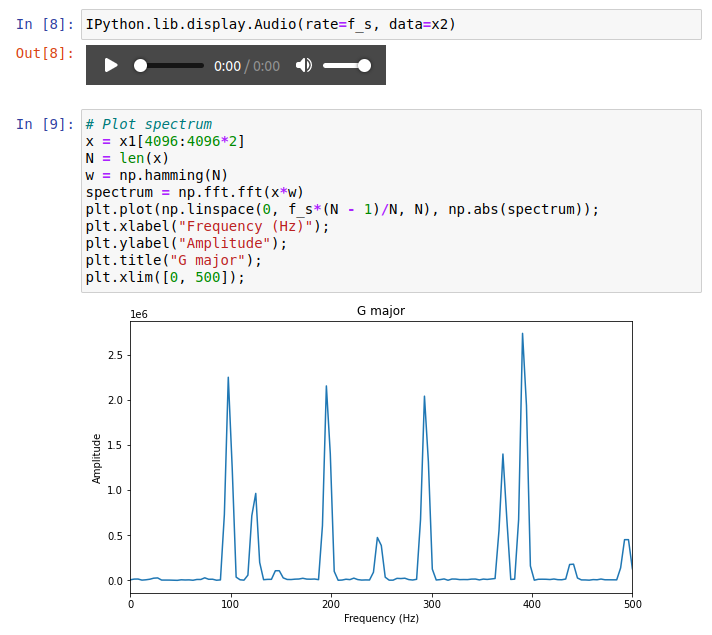

An in-class Python demo from SS414 where we are analysing music. Here we are considering the spectrum of a G-major guitar chord. Students can interactively listen and analyse different guitar chords.

An in-class Python demo from SS414 where we are analysing music. Here we are considering the spectrum of a G-major guitar chord. Students can interactively listen and analyse different guitar chords.

A big struggle when confronted with a new area is to get the bigger picture. I have seen even strong students struggle to acquire threshold concepts if they don’t have a macro-level view of where and how micro-level concepts fall within the field and relate to one another. As a practical tool to structure lectures, I have been increasingly relying on the idea of moving around the semantic plane (see Growth).

It is also essential to meet students where they are at. This is called developmental teaching (Pratt, 1998). To know how to give the students an overview of what you are going to study, it is important to know something about their background (see Growth). Concretely, this involves knowing what courses they took before, and adapting to shortcomings in previous teaching as you become aware of them.

Equipped with the lay of the land, students need to be able to build up the details as they become relevant to the problems they are facing. A lecturer can teach this by example, showing students how and where to find the relevant material, how to process it, and then how to apply it. You can help by structuring your course website clearly, pointing students to the relevant parts of the textbook, and highlighting when they are dealing with a threshold concept. By showing students where to find and how to process the relevant resources, we are equipping them to become lifelong learners. Increasingly, I try to explicitly structure my courses to require students to engage with the material themselves (see Future).

At a postgraduate level, we have an even more direct way to mentor students to become lifelong learners and engaged citizens. For these students, it is even more important to learn how to find and navigate resources themselves in order to acquire knowledge and achieve a level of mastery. This I try to do by example even more, e.g. in journal reading groups with my students and doing research myself. I try to only provide light guidance when needed. To borrow from Johan Fourie, I see myself as a Wand Dispenser: I provide the wizards of the future (research students) with the appropriate wands (skills, tools) in order to do magic of their own (research, exploration). (See more under Students and Knowledge.)

S. Brunton, “Speaking on process control distance education,” YouTube Talk, 2020.

J. M. Case, “A third approach beyond the false dichotomy between teacher- and student-centred approaches in the engineering classroom,” European Journal of Engineering Education, 2019.

J. H. F. Meyer and R. Land, “Threshold concepts and troublesome knowledge: Linkages to ways of thinking and practising,” Improving Student Learning – Theory and Practice Ten Years On, 2003.

A. I. Olszewska, E. Bondy, N. Hagler, and H. J. Kim, “A humanizing pedagogy of engagement: Beliefs and practices of award-winning instructors at a U.S. university,” Teaching in Higher Education, 2021.

D. D. Pratt, Five Perspectives on Teaching in Adult and Higher Education, Krieger Publishing Co., 1998.