Personal growth is one of the reasons I am a lecturer: if you have to explain something to someone, then you need to truly understand it. Teaching forces you to think about the big picture of a field, break it down into simpler parts, and deal with difficult questions from students.

The first class I taught was AMB124 in 2013 (before I did my PhD). I made the mistake of thinking that because I am good at giving research talks, I would be good at giving lectures. In my very first lecture, I tried to do everything on the board, but as I started, I realised that I didn’t know how to write on the board! And this was in front of 200 eager students. The lecture was a disaster. After this, for the first few weeks of the course, I would go into an empty classroom every evening and give the whole lecture, on the board, to an empty room. I learned that for me it is essential to prepare very well: I need to know beforehand exactly what I will write on the board, when I will show what on a slide, and when I will flip to a demo.

During my PhD, I tutored students at the University of Edinburgh. A crucial lesson I learned here was the importance of meeting students where they are at. The natural language processing course I tutored involved a combination of machine learning and linguistics, and was taught to students coming from either computer science or the humanities. In answering questions, it was essential to know which background a student came from.

After my postdoc in Chicago, I returned to Stellenbosch. The first course I taught was CP143. CP143 has four lecturers and relies on a common set of slides. I realised early on that just flipping through slides is a guaranteed way of getting students to fall asleep. After watching lectures from Stanford, I decided to rather work predominantly on the blackboard. Having to write things out forces students to engage and learn actively. I still use slides, but only selectively. Slides and writing on the blackboard would be interleaved with me writing computer programs on the fly to solve example problems. This combination of technologies provides a multimodal form of learning. It also forces students to look at their own handwriting afterwards and make the content their own.

Taking the above together, one of my students succinctly captured the core of my in-classroom teaching strategy in a feedback form:

Enthusiasm, class participation/engagement, combination of slides+blackboard, music/demos in Python. — Aspects of the lecturer that should be maintained, SS414 feedback, 2018.

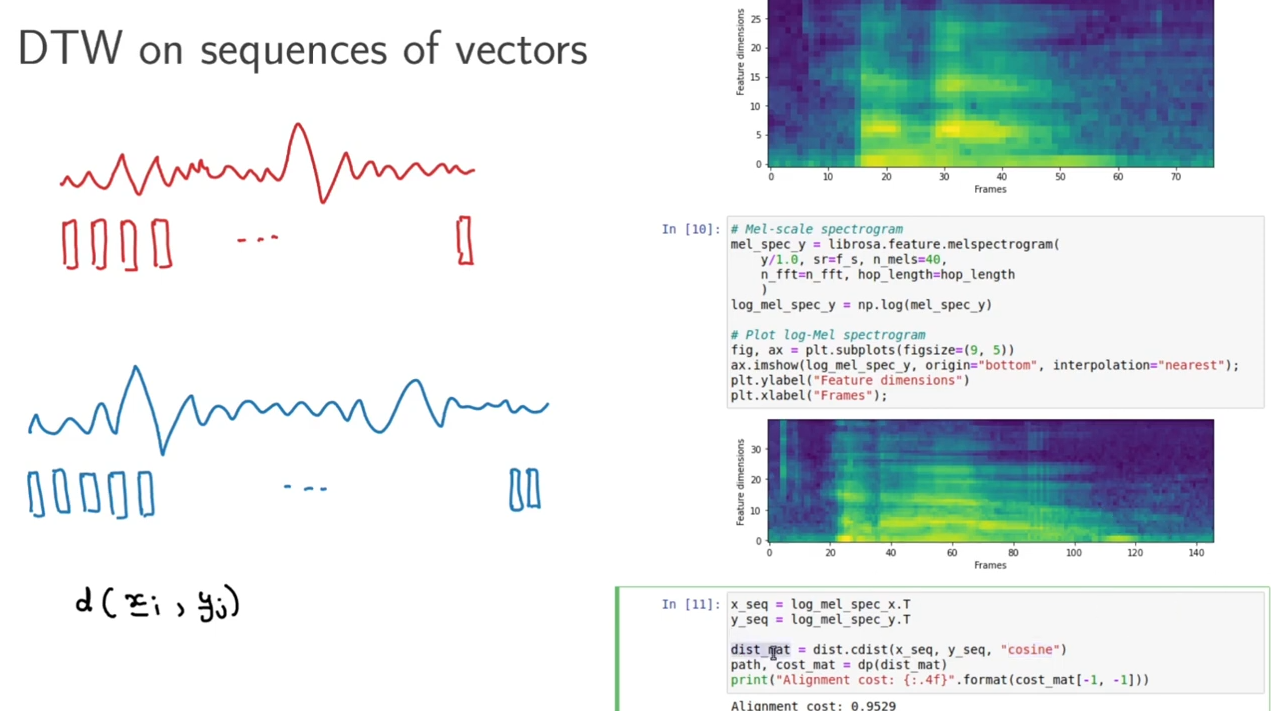

This strategy of working on the board, interleaved with selected slides, and live programming/demos is a model I continued to use for lectures. I had to adapt this strategy when we moved to online teaching in DatA414. With practice, it was relatively easy to use a partially populated slide and fill in the rest of the content in writing on a tablet as a video progresses. Later on I also incorporated demos in my lecture videos. (This blog post describes in detail how I make my videos.)

On the left, I am explaining (in writing) the underlying concepts of the code shown on the right. Full video.

On the left, I am explaining (in writing) the underlying concepts of the code shown on the right. Full video.

The handwritten notes that supplemented the text content made the slides much easier to follow and “friendlier”. Also the graphs and figures are a nice touch and tie the content together well. The student can visually follow the progression in the lecture videos, which is super effective. I’ll also mention that the content was not presented monotonously, with lots of examples and demonstrations. This made it a lot easier to stay focused and engaged in the lecture videos. Lastly, the length of the lecture videos was amazing. They hit the sweet-spot of profundity vs. attention-span. — DatA414 course feedback, 2021.

I attended PREDAC in 2021. This gave me a way to talk about and improve things that I have been intuitively doing. In 2019 I had to develop and write the Form-Bs for the registration of two new courses: DatA414 (which I then also taught for the first time in 2020) and Foundations of Deep Learning 344. Going back to these forms, I see now that I tried to structure these courses around threshold concepts (see Knowledge), despite not being aware of what this idea was called at the time. When I had to develop the new NLP817 course for the Structured MSc in Machine Learning and AI,1 I immediately started building the curriculum around the threshold concepts.

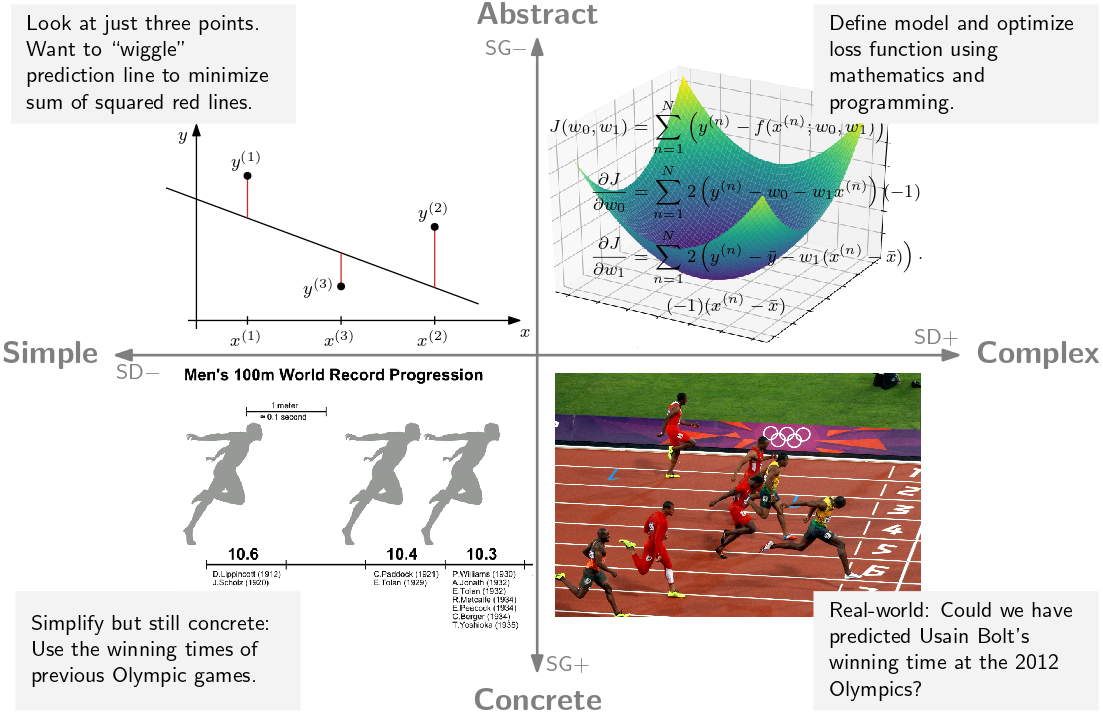

I also relied heavily on another tool that I learned during PREDAC. This tool, which I learned from Karin Wolff, is the semantic plane (Wolff et al., 2022). I myself learn best by starting with the big picture and then moving down to the more abstract fundamental concepts—and I think many students learn best in this way as well. The mistake I used to make is starting at the high level and then moving to the abstract fundamental principle, but then I won’t return and tie back the principle to the bigger picture! This is called a semantic escalator (Maton, 2013). What I am increasingly doing now is moving towards a semantic wave profile: tying the abstract back to the concrete as you proceed through a lecture. I illustrate how this is done in the first DatA414 lecture in the figure below. These observations from PREDAC also formed the basis for my contribution to our poster presentation at SoTL 2021 (Bredell et al., 2021).

The semantic plane moves from simple to complex on the x-axis, and from concrete to abstract on the y-axis. The figure illustrates how I use the plane to navigate through a lecture on simple linear regression. I start and end in the complex-concrete quadrant, moving roughly clockwise through the quadrants, but still referring back to previous quadrants as I move around.

The semantic plane moves from simple to complex on the x-axis, and from concrete to abstract on the y-axis. The figure illustrates how I use the plane to navigate through a lecture on simple linear regression. I start and end in the complex-concrete quadrant, moving roughly clockwise through the quadrants, but still referring back to previous quadrants as I move around.

At the beginning of 2022 I had to develop the new NLP817 course. This was also the first time that I would teach “post-COVID”, with a return to face-to-face lectures. Building on both pre- and post-COVID teaching experiences, I wanted to figure out an in-class-room teaching strategy that I could use going forward in the longer term. What I did was to go way back: I wrote out how each of my favourite lecturers in under- and postgraduate courses taught. There were ten lecturers. Only one made exclusive use of slides. Two made exclusive use of the blackboard. The remaining seven all used a hybrid approach, with one variant that I particularly liked: using partially completed notes and then filling them out during the lecture. This is exactly what I did during COVID, but I didn’t realise that I could do the same in in-person lectures (until doing this analysis). The value is that you can populate notes sparsely so that you don’t have to write out everything (saving time in class) but then you still require students to fill in blanked-out portions (making the notes their own). This was the model I settled on for NLP817, and you can have a look at an example of an in-person recording here.

At the beginning of 2023, I also switched to the above writing-on-partial-notes strategy for my in-person lectures in DatA414. I also made all the videos from the COVID years available to the students. Something very interesting happened in my in-person lectures. Because I knew the students had access to the content to go through on their own time, I was much more comfortable having a lecture interrupted by a student question, having them steer the discussion, and engaging with their specific thoughts. Normally I would have tried to keep a lecture on track because of time constraints, but now I could finish a lecture with e.g., “This was a great discussion. We didn’t quite get to X and Y, but you can go through that yourself and focus on aspect X.”

What I ended up with was a variant of a flipped classroom. I’ve tried a more standard flipped classroom before, where I would ask students to watch a set of videos before the lecture and then immediately start with questions and answers, but this didn’t work since students rarely engaged with the content beforehand (even if I started with a small test). But this more ad-hoc style flipped classroom style, where students in effect derail the lecture, was much more fruitful. Despite having all the videos, class attendance was also still very high. And several students mentioned that they were in fact starting to watch the videos before the lectures.

As evidence of my growth since joining Stellenbosch, I include feedback and testimonials from students, peer evaluations from colleagues, a Certificate of Recognition for teaching, and Stellenbosch University Scholarly Teacher Award which I received in 2022.

My own research is in the area of machine learning, which I am increasingly using in education as a way to do impactful research (Stellenbosch University, 2019).

In a conference paper (Hall and Kamper, 2020), we did initial work towards the bigger goal of utilising machine learning to assist learners with developing their basic mathematics skills. The idea is to identify the types of problems a user struggles with and then present them with targeted questions to improve in these areas. In the paper, we only focussed on the prediction part of the system: given a set of arithmetic questions and corresponding answers, can we predict which future questions a user will answer incorrectly? Our best model achieves an accuracy of 69% on real data.

The Language Policy of Stellenbosch University (2021) aims to promote multilingualism. In practice, this means that “[q]uestion papers in undergraduate modules are available in Afrikaans and English.” While this is noble given the benefits of mother tongue education (Kioko et al., 2014), this places a major burden on already overloaded lecturers. In engineering, many lectures therefore turn to Google Translate to provide a first-pass translation. But these automatic translations often lack the required vocabulary to cover engineering concepts. This project has the broader goal of building a machine translation system specifically for the engineering education domain. In a pilot study, I collected a small corpus of roughly 800 parallel English-Afrikaans sentences from previous assessments in E&E. I built an initial machine translation systems on this data, and presented the work at SoTL 2022 (Kamper, 2022).

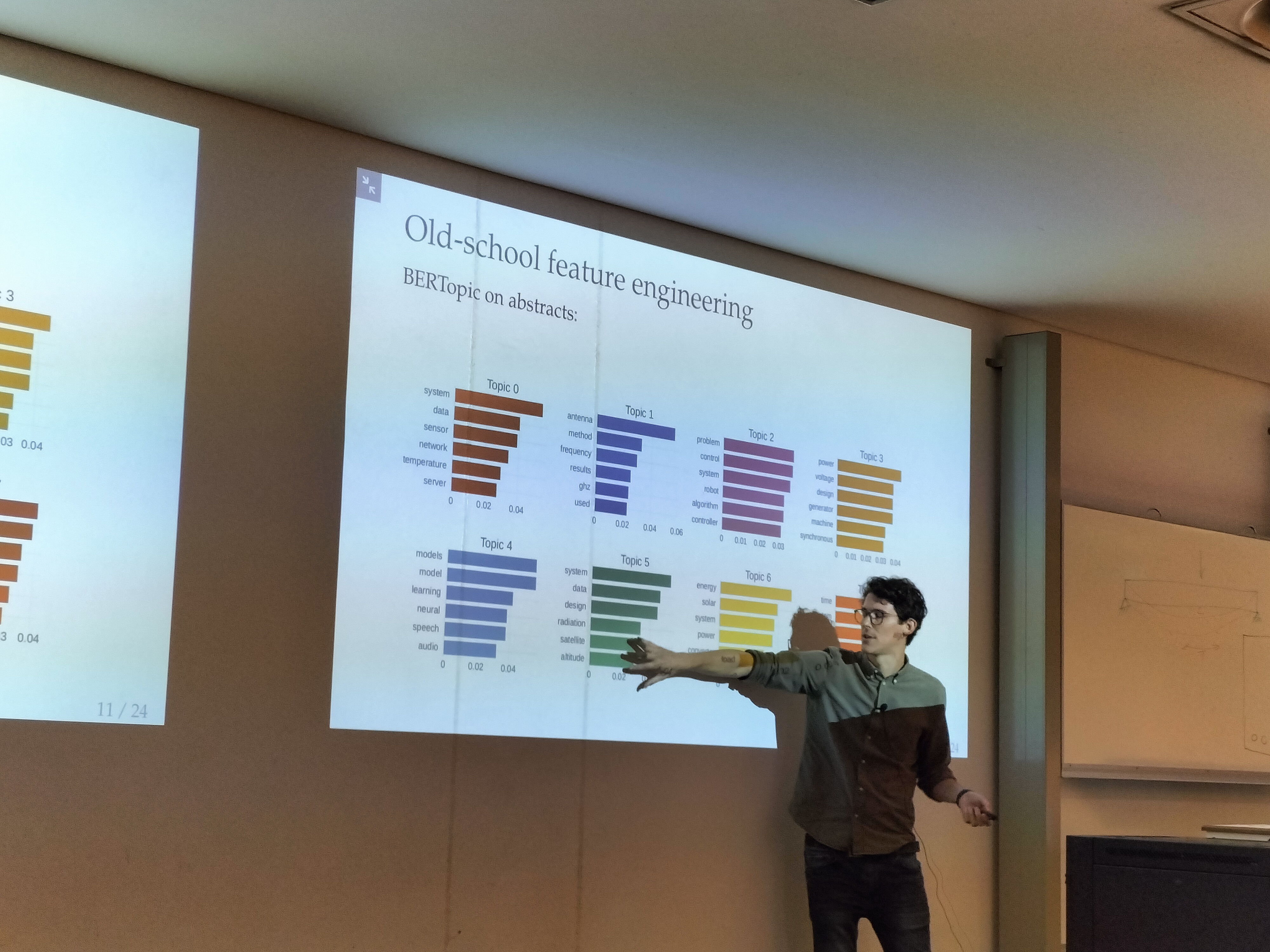

Forming part of the Recommended Engineering Education Project (REEP) at Stellenbosch, I recently collaborated with Carla Niehaus and Karin Wolff to see if we could use machine learning to gain a better understanding of the assessment practices of capstone projects. We collected a dataset of previous E&E capstone project reports with the marks awarded, and then trained machine learning models to predict a mark given a report as input. The models showed marks are most affected by report length and the research area of the project. We also had a new set of examiners re-examine the reports in our dataset. This revealed a large discrepancy of roughly 12% between examiners. This supports previous work showing the subjectivity involved in assessments, leading to high inter-assessor variability. I shared these findings in a feedback session with lecturers in our department (lecturers from other departments also attended); this led to initial discussions to improve assessment practices and consistency. This work has recently been accepted as a full paper at the World Engineering Education Forum (WEEF), the premier conference on engineering education (Kamper et al., 2023).

I had an engagement session with our department, sharing our findings showing the subjective nature of capstone project assessments.

I had an engagement session with our department, sharing our findings showing the subjective nature of capstone project assessments.

J. R. Bredell, E. Burger, H. Kamper, and H. Pretorius, “Individual and collaborative reflections on teaching and learning,” SoTL, 2021.

T. Hall and H. Kamper, “Towards improving human arithmetic learning using machine learning,” PRASA, 2020.

H. Kamper, “Machine translation of engineering assessments: Data collection for a pilot study,” SoTL, 2022.

H. Kamper, C. Niehaus, and K. Wolff, “Using machine learning to understand assessment practices of capstone projects in engineering,” WEEF, 2023.

A. N. Kioko, R. W. Ndung’u, M. C. Njoroge, and J. Mutiga, “Mother tongue and education in Africa: Publicising the reality,” Multilingual Education, 2014.

K. Maton, “Making semantic waves: A key to cumulative knowledge-building,” Linguistics and Education, 2013.

Stellenbosch University, “Vision 2040 and strategic framework 2019–2024,” Online, 2019.

Stellenbosch University, “Revision of language policy,” Online, 2021.

K. Wolff, K. Kruger, R. Pott, and N. de Koker, “The conceptual nuances of technology-supported learning in engineering,” European Journal of Engineering Education, 2022.

I teach this additional course for the Faculty of Science using my extra engineering contract hours. ↩