I teach at one of the top institutions in Africa. But even here in our wealthy town, we can see the socio-economic challenges facing South Africa and the rest of the continent: inequality, illiteracy, and limitations in access to education. Globally, we will increasingly be faced with the problems of climate change and sustainable energy generation. While I don’t have all the answers, I try to show the students how the knowledge they acquire can be used to better understand and address these challenges. E.g. in one of my DatA414 lectures,1 we look at how the percentage of households with low socioeconomic status in a neighbourhood affects median house prices. For the 2020 DatA414 course project, students had to develop and implement a model to predict future wind speeds based on past measurements. By showing students the relevance of what they are learning, I hope to create excitement about the material, leading to engagement (Teaching Philosophy, goal 1).

Since broader community engagement is also one of the main purposes of universities within society (Badat, 2009), I have increasingly been trying to reach an even wider audience outside of just my classroom at Stellenbosch. One way is through the Deep Learning Indaba, one of the largest winter schools in AI and machine learning in the world. I was an organiser of the 2018 Indaba at Stellenbosch, attended by around 550 students and researchers. I taught on speech and natural language processing for low-resource languages at the 2019 Indaba in Kenya. For the 2022 Indaba in Tunisia, I took some of my in-person NLP817 lecture recordings and compiled them in a playlist for the Indaba’s natural language processing practical. I did the same for the 2023 Indaba in Ghana.

Me teaching at the Deep Learning Indaba 2019 in Nairobi, Kenya.

Me teaching at the Deep Learning Indaba 2019 in Nairobi, Kenya.

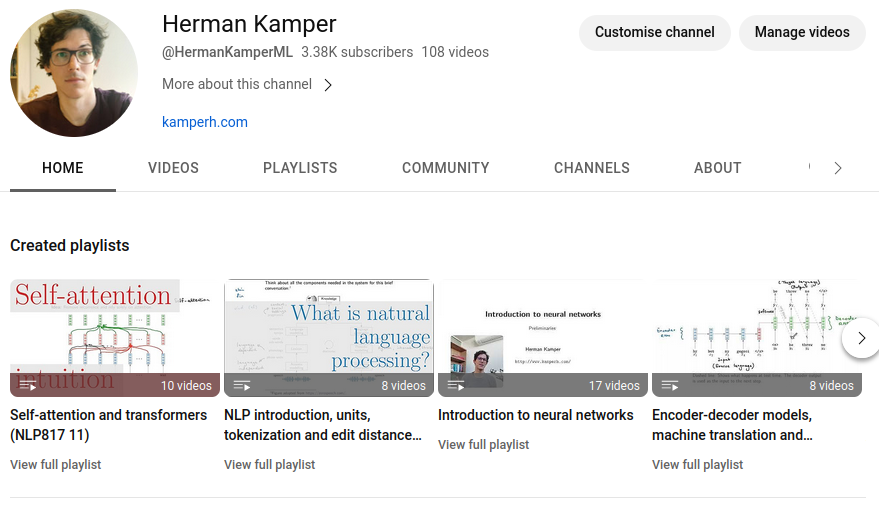

The switch to online teaching during COVID in 2020 also resulted in a great opportunity to engage more broadly outside of the university. During this time, I started to post my lecture videos on YouTube, a practice I continued after returning to in-person teaching in 2021. This allows anyone to benefit from the content. I currently have roughly 3.4k subscribers and several videos with around 20k views. This also allows Stellenbosch students to access these resources after they have graduated. As far as I know, my DatA414 lecture videos are used or referred to in at least four other courses at Stellenbosch (DatA324, Statistical Learning Theory 812&842, CS E414). I also share example code snippets such as this one on GitHub. I got the following email from a student not taking any of my courses:

I am currently a CS315 student and can’t thank you enough for the wonderful content you share so openly on GitHub and YouTube. It really helps. It is amazing how you explain such complicated concepts in an understandable way! — Translation of original email in Afrikaans, 2022.

My YouTube channel, HermanKamperML.

My YouTube channel, HermanKamperML.

Since I was an undergraduate student in engineering at Stellenbosch (2006-2009), the composition of classes has changed substantially, with more female students and students of colour joining the faculty. (Despite great strides, this change is still too slow.) This means that we are now teaching to students coming from very different academic, financial, linguistic and cultural backgrounds. Although this can be challenging, it is also a privilege to play a small role in helping these students become engaged citizens—each in their own unique context.

As part of my Teaching Philosophy (goal 1), I believe it is important to make students excited about the work. One way is to give examples speaking to their interests. This is challenging given the diversity of our students. But I have found two areas that almost all students show an interest in: music and language. Within the first week of SS414, I normally put up a sheet on which any student can make recommendations about songs or artists that they enjoy. Most of the digital signal processing concepts in this course can be illustrated on a music signal. Through the semester I would then update my Python demos so that I e.g. apply a new filter to one of the recommended songs. My own research applies machine learning to problems in speech and language processing, and I often show examples from these areas in class. I recall when I showcased a model that we developed for Xitsonga. A quiet student, always sitting at the back of the class, jumped up saying: “This is my language!” This student was able to interpret the model’s output for me and the rest of the class.

I have co-supervised and worked with master’s students at the University of Edinburgh and the University of Chicago. When I started at Stellenbosch in 2017, I was amazed to find that our final-year and postgraduate students are on par or better than many of the students at these international institutions. Often, instead of giving explicit instructions, my role is simply to remove barriers for these students, just making sure there isn’t anything prohibiting them to learn and proceed on their own. I.e., I’m really just handing them a wand.

The current advances in machine learning and AI are changing what I research, what I teach, and how I teach. Because I teach courses on machine learning and natural language processing, I am changing my courses so that they cover both fundamental concepts that will not change as well as the latest developments. E.g. in NLP817, this has meant including a new unit dedicated to transformers, the underlying technology behind GPT (the “T” stands for transformer). I have also given public talks on GPT, specifically on how it intersects with my Christian world view.

As in higher education institutions around the world, Stellenbosch is grappling with the questions of how generative AI will affect the ways we teach and assess. We should keep in mind that the goals of learning and teaching and the values we want to instil in our students have not changed. Accountability remains a core principle, as the draft Stellenbosch guidelines on AI use also clearly states (Stellenbosch University, 2023). E.g. when AI is used for writing, the human author is still ultimately responsible for making sure that what they produce with the help of AI is factually correct, will not cause harm, and that credit is properly given to the relevant human sources.

While our goals and values have not changed, technology can help us better achieve them. In this regard, the Stellenbosch draft policy is too prohibitive. It creates the impression that students should be wary of employing AI as a way to aid learning, e.g. “you need to guard against outsourcing your learning to AI”. It is impossible to outsource learning. Imagine telling students “you need to guard against outsourcing your learning to Google Scholar”. Students should be encouraged to use Google Scholar! In the same way, broad use of AI should be encouraged in order to improve learning. The use of AI tools for writing should also be strongly encouraged. A student should be able to use AI generated text without alteration if it conveys the message that they want to deliver (while adhering to the accountability principle, e.g. by ensuring that the content does not amount to blatant plagiarism of human content.) We live in an increasingly fast-paced high-demand society; if mundane tasks can be outsourced to a machine, then students should be encouraged and taught to do so.

S. Badat, “The role of higher education in society: Valuing higher education,” HERS-SA Academy, 2009.

Stellenbosch University, “Draft interim SU guidelines on allowable AI use and academic integrity in assessment,” 2023.

The abbreviations for the course names are given under Background. ↩